From February 14 to 16, 2024, a Human Rights training was conducted for a group of class representatives aged 12 to 18. These young elected delegates had no prior knowledge of the subject. The primary objective of this training was to deepen their understanding of Human Rights, enhance their sense of civic responsibility, and develop their leadership skills. To assess the impact of this initiative, interviews with participants were conducted in April and May 2024. The results highlight a clear shift toward a more grounded and proactive approach to citizenship.

By Murielle Gemis – On the occasion of December 10, 2024, the anniversary of Human Rights.

Since taking over as principal of Mercelis School in Ixelles, Mr. Andy Wattié has been working to establish a sustainable system of class representatives. Supported by his teaching staff, this initiative has drawn on the expertise of Murielle Gemis, founder of HumanRights4Prosperity, an organization dedicated to training and raising awareness among entrepreneurial actors about Human Rights. As a psychopedagogue, Murielle Gemis recognized the potential of young class representatives to become future leaders and entrepreneurs, capable of promoting civic and responsible values. She proposed a training program for the delegates, leveraging a model that has already proven successful in more challenging contexts. The training was delivered with the collaboration of Quentin Delassias, a student intern, and Danielle Ferron, a teacher and expert in implementing class representative systems in schools. This initiative also incorporated resources generously provided by humanitarian partner Youth for Human Rights. The ambitious project aims not only to strengthen the role of class representatives but also to provide them with a solid foundation to become responsible and engaged individuals in their future academic and professional endeavors.

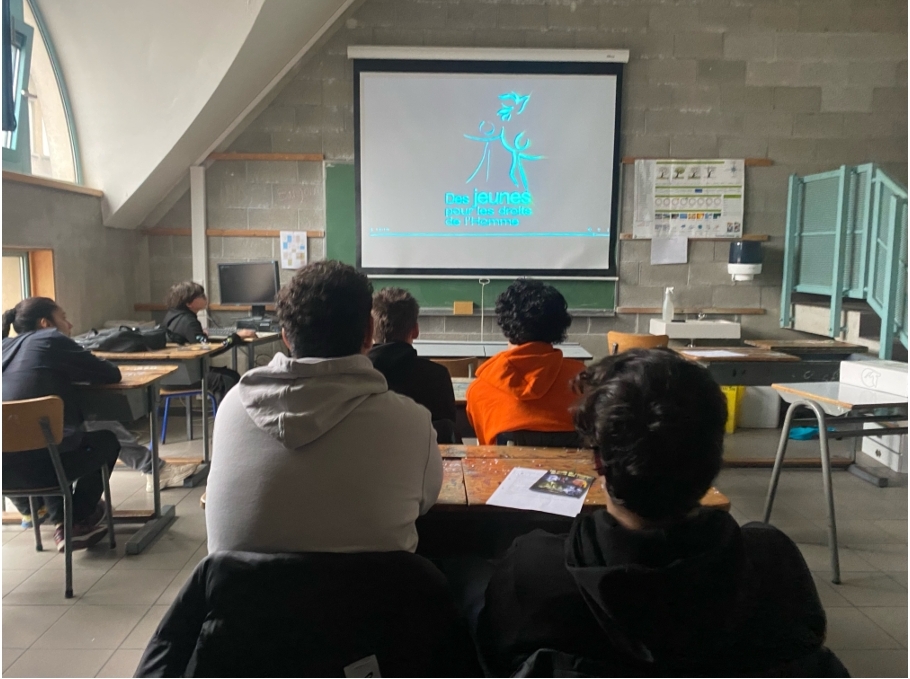

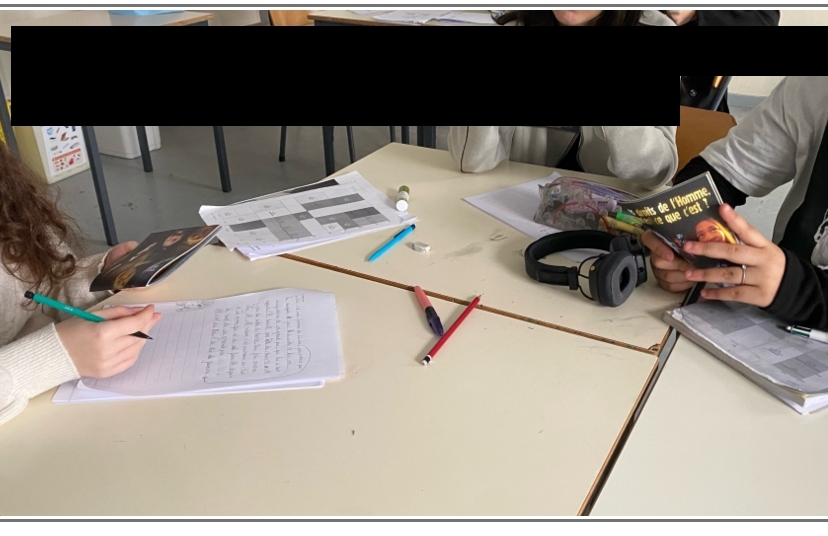

This three-day training program was organized into specific modules covering a wide range of topics. These included survival dynamics and human rights and freedoms, clarification of the terms and principles enshrined in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and practical skills such as establishing group rules and effective leadership communication.

Participants also gained insights into organizations dedicated to promoting Human Rights, including those operating in Africa, thanks to a live Zoom session with Kabine Doumbia, President of the NGO ASDRAD.Mali. One participant shared, “I learned that there are Human Rights organizations in Africa too,” while another added, “There are different rights that can be defended.”

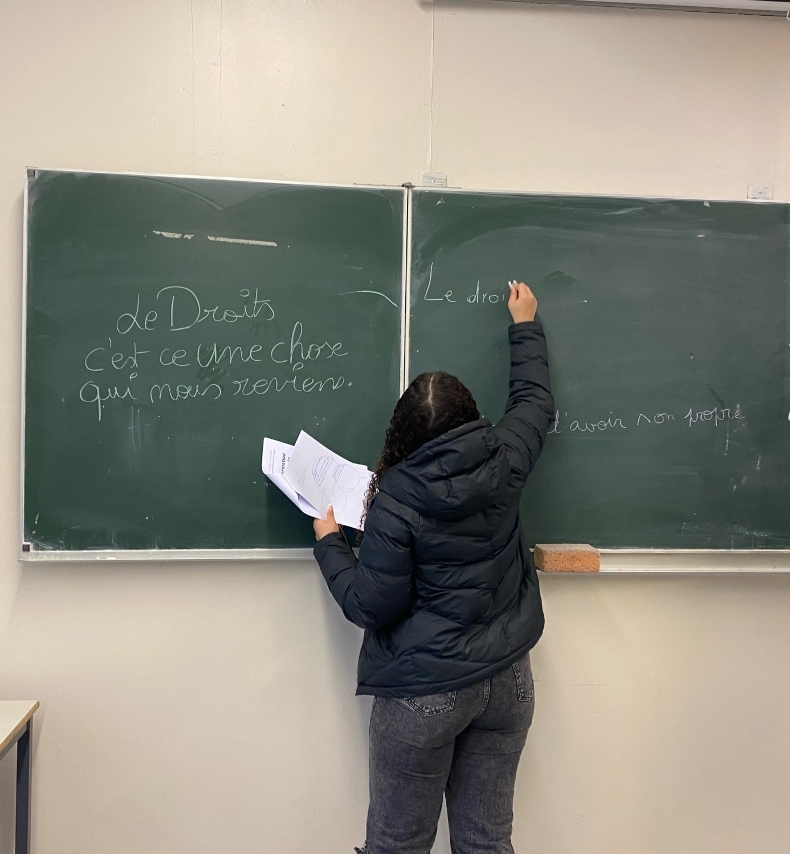

At the conclusion of the training, the delegates visited individual classrooms to share essential tools with a majority of the school’s students. These tools included age-appropriate videos illustrating the 30 articles of Human Rights and the Youth for Human Rights handbook. This final initiative allowed the delegates to put their knowledge into practice by communicating it to their peers in their own words, effectively promoting the articles of Human Rights on a broader scale.

Participants’ Perspectives and Future Challenges

To assess the achievement of the set objectives, a follow-up survey was conducted, revealing significant changes in the participants’ behavior, including improved interpersonal relationships, greater respect for others, and a deeper understanding of human rights, observed both by the delegates themselves and their peers. Following these results, the young participants were also asked to identify areas where they might need additional support to better implement the learned concepts, as well as to suggest supplementary resources or training that could be beneficial to them.

Here is a summary of the responses obtained, accompanied by illustrative verbatim statements from the participants.

The participants retained various fundamental rights such as “the right to expression, to speak, to vote, to move freely, and more.” The training helped participants realize the extent of their personal freedoms. “I discovered I had more freedom thanks to these rights. I have the freedom to speak my language.” The videos used during the training had a significant impact, making the concepts more concrete and realistic. “I liked the videos, especially how they were presented; it seemed real.” “What I liked most was the notebook with the videos because it was interesting and I learned new things, like being imprisoned for no reason.” The distinction between dictatorship and leadership was particularly striking for some participants. “The part explaining the difference between dictator, chief, and leader.” Participants understood that human rights apply to everyone, regardless of skin color or other differences. “Human rights are for everyone, there are no differences regardless of skin color.” Some participants noted an improvement in their language skills and communication abilities. “I have an improvement in French and I speak better with others.” They highlight that they have developed a new perception of others and conflict situations: “I see people differently now because before, I didn’t have this perception of others.””The right to live made me reflect a lot on what happens in some war-torn regions where this right is absolutely not respected. If war ever comes to us, I don’t want to be a part of it.” Several participants started to act differently, showing more respect and courtesy towards others. “I stand up more often for elderly people, whereas before it was quite rare.” “I respect the pedestrian crossing.” “I’ve learned to set rules and I’m much more disciplined on the street and at home. For example, I respect older people now; one day on the tram, I got up to give my seat to an older person when before I wouldn’t have done that.”

Participants also began intervening to promote respect for others’ rights. “I respect those who are smaller than me, I no longer get into fights. My environment is calmer.” “In class, I make it clear that we should not judge others. For example, one day the whole class was teasing A with a nickname, ‘Mayget,’ and I intervened by asking them how they would have felt if they were in A’s place. At first, they continued. Today, it’s less harsh and less insulting.”

“In my family, with my younger brothers. When they insult each other or are violent towards each other, now I intervene even if it’s later. I sit them down on the couch and explain that violence is not helpful. During this interview, I think I will show them the videos you showed us.”

Participants noted improvements in their behavior and interactions with others. “I am much less shy than before. The fact that we were in a group, that we talked together, it opened me up to others and I am less shy now.”””I am much calmer and more at ease now. I can stay still for longer without feeling excited or constantly moving around.””

“”When I am with R, before I never listened but I always talked about myself; now we share what we have to say together.”

“I listen much more when someone speaks to me, I take the time to listen before I speak myself.”

“The video about discrimination, I apply it by making my classmates understand that it’s wrong to leave someone alone. I myself am more vigilant not to leave others alone.”

“I talked with my class about this freedom of expression but in a calm manner.”

Participant A: “I respect those who are younger than me now, and I no longer get into fights. My environment is much calmer.”

Participant B: “I’ve noticed that the delegates who participated in the training are much more respectful than before. For example, little H., who was with us, is much kinder and calmer in the playground and when we talk together.”

The feedback from participants regarding additional support needs after the training reveals clear aspirations and specific requests to enhance their engagement and the practice of the learned concepts. Some express a desire to become more involved in community actions: “Help me find an association I can support because I want to get involved.” They also suggest that experienced teachers, like Mr. M. (religion teacher), could play a key role in facilitating this involvement. Public speaking is another area where these young individuals seek to improve. A delegate explains, “I want to feel even more comfortable speaking in public, especially as a class delegate. I want to be able to share my ideas with a large group.” There is also a consensus on the need to extend the benefits of the training to the entire school: “I think this training should be given to the whole school because it brings discipline, communication, and it helped me feel more comfortable in class.” Finally, some call for a return to previous practices to strengthen language skills: “Maybe in French class, we could focus more on speaking skills like we used to do in primary school.”

Conclusion: For Active and Responsible Citizenship

These testimonials illustrate the concrete and positive impact of a human rights training program within a school context. It has allowed participants to better understand and internalize the principles of human rights, increasing their social and civic awareness, which leads to the development of practical skills and the adoption of a more proactive and engaged attitude in favor of these fundamental rights of 1948. For example, Participant A demonstrated personal improvement by respecting younger peers and avoiding conflicts, contributing to a more peaceful environment. Participant B observed and confirmed these changes, noting that the improvement in “small H.’s” behavior had a ripple effect, positively influencing his peers and fostering an atmosphere of respect and harmony within the group. These changes are not only personal but also recognized by peers, validating the effectiveness and relevance of the teachings provided. This underscores the transformative impact of a comprehensive human rights training on both individual and collective behavior. Beyond these immediate results, this initiative is part of a sustainable approach. Indeed, a third-degree teacher, inspired by the enthusiasm of young delegates who were sharing human rights concepts class by class, regretted the lack of participation from third-degree students who were on a placement at the time of the training. Concerned about filling this gap, he decided to integrate human rights into one of his educational programs developed in collaboration with the SOS Jeunes – Quartier Libre asbl association. This approach aims to embed these teachings in a dynamic that is renewed each year, reaching a wider audience and ensuring the sustainability of the training’s impact. In the current context of teacher training reform, it would be particularly relevant to equip future educators with such frameworks. Integrating modules on the 1948 Human Rights into their training could provide them with the necessary tools to develop innovative teaching practices and raise awareness among future generations about these fundamental values. This sustainable framework would ensure the continuous reinforcement of responsible behaviors and civic values, while establishing human rights as an essential pillar of education, in line with Belgium’s commitment when signing the noble Charter in 1948.

Gemis Murielle